Polygyny

Although polygyny is now illegal in most Western societies, it was very much a part of Judeo-Christian history and appeared to be a privilege of rulers and elites. The Old Testament includes many references to men with multiple wives. King David and his son, King Solomon, are both said to have had hundreds of wives and concubines, though such extravagant numbers are likely to be exaggerated. In early Medieval Europe, rulers practiced polygyny to ensure that they would have a male heir. And rulers took more than one wife as a way to build alliances with or annex neighboring kingdoms. Polygyny continues to be a mark of great wealth or high status in many societies, but in those societies only the very wealthy are expected to (or can) support more than one wife. Some Muslim societies, especially Arabic-speaking ones, still view polygyny in this light. But a man does not always have to be wealthy to be polygynous; indeed, in some societies in which women are important contributors to the economy, it seems that men try to have more than one wife to become wealthier.

Among the Siwai, a society in the South Pacific, status is achieved through feast giving. Pork is the main dish at these feasts, so the Siwai associate raising pigs with prestige. The great interest in pigs also sparks an interest in wives, because in Siwai society women raise the food needed to feed pigs. Thus, although having many wives does not in itself confer status among the Siwai, the increase in pig herds—and prestige—that can result offers men a strong incentive to be polygynous.83 Polygynously married Siwai men do seem to have greater prestige, but they also complain that a household with multiple wives is difficult. Sinu, a Siwai, described his plight:

There is never peace for a long time in a polygynous family. If the husband sleeps in the house of one wife, the other one sulks all the next day. If the man is so stupid as to sleep two consecutive nights in the house of one wife, the other one will refuse to cook for him, saying, “So-and-so is your wife; go to her for food. Since I am not good enough for you to sleep with, then my food is not good enough for you to eat.” Frequently the co-wives will quarrel and fight. My uncle formerly had five wives at one time and the youngest one was always raging and fighting the others. Once she knocked an older wife senseless and then ran away and had to be forcibly returned.84

Sororal and Nonsororal Polygyny

Jealousy and conflict between co-wives seem not to be present in a minority of polygynous societies. Margaret Mead reported that married life among the Arapesh of New Guinea, even in polygynous marriages, was “so even and contented that there is nothing to relate of it at all.”85 What might explain such harmony? One possible explanation is that the co-wives are sisters. Sororal polygyny, a man’s marriage to two or more sisters, seems to work because siblings, having grown up together, are more likely to get along and cooperate than co-wives who practice nonsororal polygyny—that is, who are not related. Indeed, a recent cross-cultural study confirms that persistent conflict and resentment were all-too-common in societies with nonsororal polygyny. The most commonly reported complaint was insufficient access to the husband for sex and emotional support.86

Perhaps because conflict is so common among co-wives, particularly with nonsororal polygyny, polygynous societies appear to have invented similar customs to try to lessen conflict and jealousy in co-wives:

-

Whereas sororal co-wives nearly always live under the same roof, co-wives who are not sisters tend to have separate living quarters. Among the African Plateau Tonga, who practice nonsororal polygyny, co-wives live in separate dwellings and the husband shares his personal goods and his favors among his wives according to principles of strict equality. The Crow of the northern plains of North America, on the other hand, practiced sororal polygyny; their co-wives usually shared a tepee.

-

Co-wives have clearly defined equal rights in matters of sex, economics, and personal possessions. For example, the Tanala of Madagascar require the husband to spend a day with each co-wife in succession. Failure to do so constitutes adultery and entitles the slighted wife to sue for divorce and alimony of up to one-third of the husband’s property. Furthermore, the land is shared equally among all the women, who expect the husband to help with its cultivation when he visits them.

-

Senior wives often have special prestige. The Tonga of Polynesia, for example, bestow the status of “chief wife” upon the first wife. Her house stands to the right of her husband’s and is named the “house of the father.” The other wives are called “small wives,” and their houses are to the left of the husband’s. The chief wife has the right to be consulted first, before the small wives, and her husband is expected to sleep under her roof before and after a journey. Because later wives are often favored because they tend to be younger and therefore more attractive, practices that elevate the first wife’s status may serve as compensation for her loss of physical attractiveness by increased prestige.87

Why Is Polygyny a Common Practice?

Although jealousy and conflict are noted as common problems in polygynous marriage, the practice may also offer social benefits. Married females as well as males in Kenya believed that polygyny provided economic and political advantages, according to a study conducted by Philip and Janet Kilbride. Because they tend to be large, polygynous families provide plenty of farm labor and extra food that can be marketed. They also tend to be influential in their communities and are likely to produce individuals who become government officials.88 And in South Africa, Connie Anderson found that women choose to be married to a man with other wives because the other wives could help with child care and household work, provide companionship, and allow more freedom to come and go. Some women said they chose polygynous marriages because there was a shortage of marriageable males.89

How can we account for the fact that polygyny is allowed and often preferred in most of the societies known to anthropology? Ralph Linton suggested that polygyny derives from a general male primate urge to collect females.90 But if that were so, then why wouldn’t all societies allow polygyny? Other explanations of polygyny have been suggested. We restrict our discussion here to those that statistically and strongly predict polygyny in worldwide samples of societies.

One theory is that polygyny will be permitted in societies that have a long postpartum sex taboo.91 In these societies, a couple must abstain from intercourse until their child is at least a year old. John Whiting suggested that couples abstain from sexual intercourse for a long time after their child is born for health reasons. A Hausa woman reported:

A mother should not go to her husband while she has a child she is suckling. If she does, the child gets thin; he dries up, he won’t be strong, he won’t be healthy. If she goes after two years it is nothing, he is already strong before that, it does not matter if she conceives again after two years.92

The symptoms the woman described seem to be those of kwashiorkor. Common in tropical areas, kwashiorkor is a protein-deficiency disease that occurs particularly in children suffering from intestinal parasites or diarrhea. If a child gets protein from mother’s milk during its first few years, the likelihood of contracting kwashiorkor may be greatly reduced. By observing a long postpartum sex taboo, and thereby ensuring that her children are widely spaced, a woman can nurse each child longer. Consistent with Whiting’s interpretation, societies whose principal foods are low-protein staples, such as taro, sweet potatoes, bananas, breadfruit, and other root and tree crops, tend to have a long postpartum sex taboo. Societies with long postpartum sex taboos also tend to be polygynous. Perhaps, then, a man’s having more than one wife is a cultural adjustment to the taboo. As a Yoruba woman said,

When we abstain from having sexual intercourse with our husband for the two years we nurse our babies, we know he will seek some other woman. We would rather have her under our control as a co-wife so he is not spending money outside the family.93

Even if we agree that men will seek other sexual relationships during the period of a long postpartum sex taboo, it is not clear why polygyny is the only possible solution to the problem. After all, it is conceivable that all of a man’s wives might be subject to the postpartum sex taboo at the same time. Furthermore, there may be sexual outlets outside marriage.

Another explanation of polygyny is that it is a response to an excess of women over men. Such an imbalanced sex ratio may occur because of the prevalence of warfare in a society. Because men and not women are generally the warriors, warfare almost always takes a greater toll of men’s lives. Given that almost all adults in noncommercial societies are married, polygyny may be a way of providing spouses for surplus women. Indeed, there is evidence that societies with imbalanced sex ratios in favor of women tend to have both polygyny and high male mortality in warfare. Conversely, societies with balanced sex ratios tend to have both monogamy and low male mortality in warfare.94

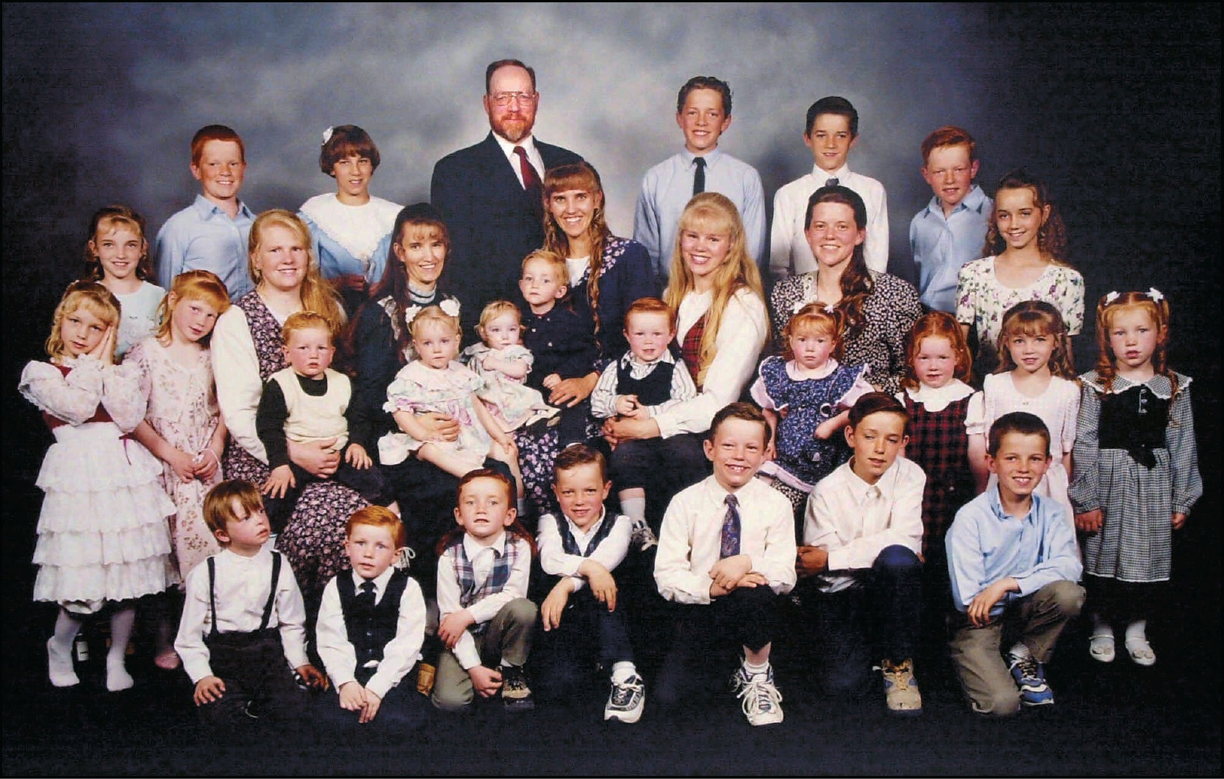

Even though illegal, many in the state of Utah still practice polygyny. The husband in the top row of this picture has five wives and 35 children.

A third explanation is that a society will allow polygyny when men marry at an older age than women. The argument is similar to the sex-ratio interpretation. Delaying the age when men marry would create an artificial, though not an actual, excess of marriageable women. Why marriage for men is delayed is not clear, but the delay does predict polygyny.95

Is one of these explanations better than the others, or are all three factors—long postpartum sex taboo, imbalanced sex ratio in favor of women, and delayed age of marriage for men—important in explaining polygyny? One way of trying to decide among alternative explanations is to do what is called a statistical-control analysis, which allows us to see if a particular factor still predicts when the effects of other possible factors are removed. In this case, when the possible effect of sex ratio is removed, a long postpartum sex taboo no longer predicts polygyny and hence is probably not a cause of polygyny.96 But both an actual excess of women and a late age of marriage for men seem to be strong predictors of polygyny. Added together, these two factors predict polygyny even more strongly.97

Behavioral ecologists have also suggested ecological reasons why both men and women might prefer polygynous marriages. If there are enough resources, men might prefer polygyny because they can have more children if they have more than one wife. If resources are highly variable and men control resources, women might find it advantageous to marry a man with many resources even if she is a second wife. A recent study of foragers suggests that foraging societies in which men control hunting or fishing territories are more likely to be polygynous. This finding is consistent with the theory, but the authors were surprised that control of gathering sites by men did not predict polygyny.98 The main problem with the theory of variable resources and their marital consequences is that many societies, particularly in the “modern” world, have great variability in wealth but little polygyny. Behavioral ecologists have had to argue, therefore, that polygyny is lacking because of socially imposed constraints. But why are those constraints imposed?

The sex-ratio interpretation can explain the absence of polygyny in most commercialized modern societies. Very complex societies have standing armies, and in such societies male mortality in warfare is rarely as high proportionatelyas in simpler societies. Also, with commercialization, there are more possibilities for individuals to support themselves in commercialized societies without being married. The degree of disease in the environment may also be a factor.

Bobbi Low has suggested that a high incidence of disease may reduce the prevalence of “healthy” men. In such cases, it may be to a woman’s advantage to marry a healthy man even if he is already married, and it may be to a man’s advantage to marry several unrelated women to maximize genetic variation (and disease resistance) among his children. Indeed, societies with many pathogens are more likely to have polygyny.99 A recent cross-cultural study compared the degree of disease as an explanation of polygyny with the imbalanced sex-ratio explanation. Both were supported. The number of pathogens predicted particularly well in more densely populated complex societies, where pathogen load is presumably greater. The sex-ratio explanation predicted polygyny particularly well in sparser, nonstate societies.100 Nigel Barber used data from modern nations to test these ideas. He found that sex-ratio and pathogen stress predicted polygyny in modern nations as well.101

Watch

Polygyny around the world