Economic Aspects of Marriage

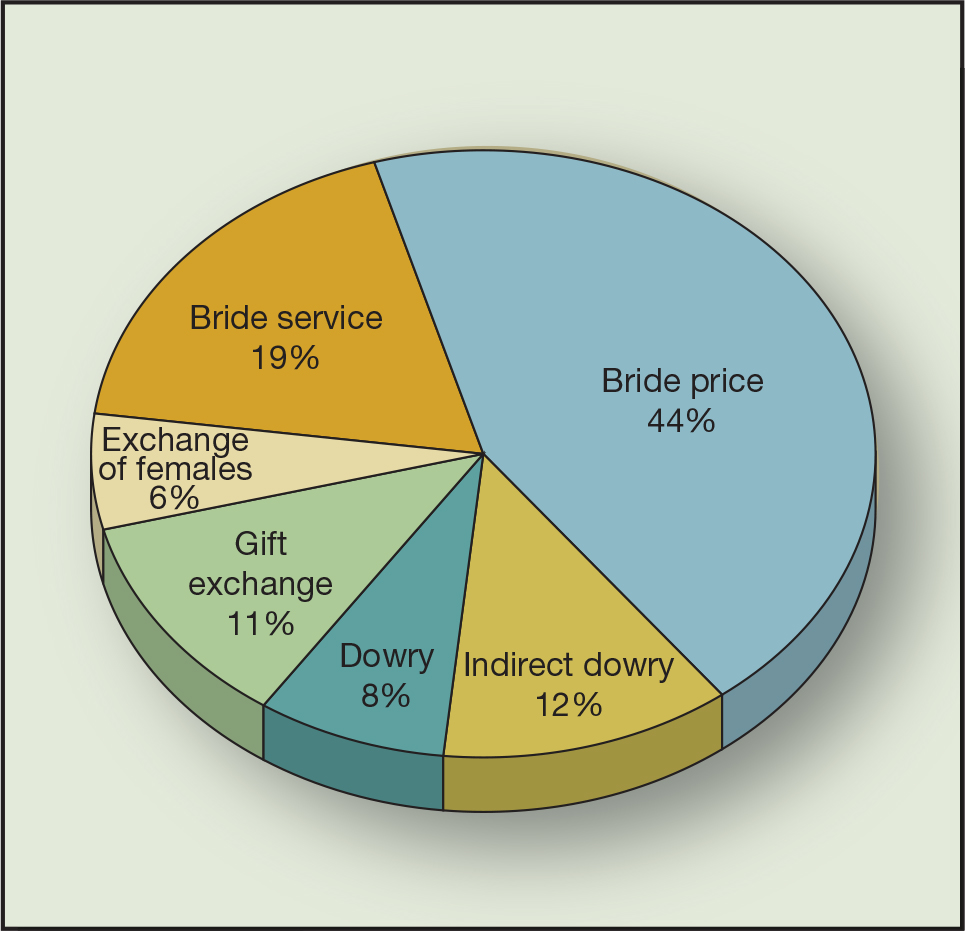

“It’s not man that marries maid, but field marries field, vineyard marries vineyard, cattle marry cattle,” goes a German peasant saying. In its down-to-earth way, the expression states a reality in many societies: Marriage involves economic considerations. In our culture, economic considerations may or may not be explicit. However, in about 75 percent of the societies known to anthropology,28 one or more explicit economic transactions take place before or after the marriage. The economic transaction may include any of several forms: bride price, bride service, exchange of females, gift exchange, dowry, or indirect dowry. The distribution of those forms among societies that have economic marriage transactions is shown in Figure 19.1 .

Figure 19.1

Distribution of Economic Marriage Transactions Among Societies That Have Them

Note that there are societies in the ethnographic record (25 percent) that lack any substantial economic transactions at marriage.

Source: Based on data from Schlegel and Eloul 1988, 291–309.

Bride Price

A gift of money or goods from the groom or his kin to the bride’s kin is known as bride price or bride wealth. The gift usually grants the groom the right to marry the bride and the right to her children. Of all the forms of economic transaction involved in marriage, bride price is the most common. In one cross-cultural sample, 44 percent of societies that had economic transactions at marriage practiced bride price; in almost all of those societies, the bride price was substantial.29 Bride price is practiced all over the world, but it is especially common in Africa and Oceania. Payment may be made in different currencies; livestock and food are two of the more common. With the increased importance of commercial exchange, money has increasingly become part of bride price payments. Among the Nandi, the bride price consists of five to seven cattle, one or two sheep and goats, cowrie shells, and money equivalent to the value of one cow. Even in unusual female-female marriages, the female “husband” must pay a bride price to arrange the marriage and be considered the “father.”30

The Subanun of the Philippines exact a high bride price—several times the annual income of the groom plus three to five years of bride service (described in the next section).31 Among the Manus of the Admiralty Islands of New Guinea, a groom requires an economic backer, usually an older brother or an uncle, if he is to marry, but it will be years before he can pay off his debts. Depending on the final bride price, payments may be concluded at the time of the marriage, or they may continue for years afterward.32

Despite the connotations that bride price may have, the practice does not reduce a woman to the position of slave. It is, nevertheless, associated with societies in which women have relatively low status. The bride price may be important to the woman and her family. Indeed, the fee they receive can serve as a security. If the marriage fails through no fault of hers and the wife returns to her kin, the family might not return the bride price to the groom. On the other hand, the wife’s kin may pressure her to remain with her husband, even though she does not wish to, because they do not want to return the bride price or are unable to do so. A larger bride price is associated with more difficulty in obtaining a divorce.33

What kinds of societies are likely to have the custom of bride price? Cross-culturally, societies with bride price are likely to practice horticulture and lack social stratification. Bride price is also likely where women contribute a great deal to primary subsistence activities34 and where they contribute more than men to all kinds of economic activities.35 Although these findings might suggest that women are highly valued in such societies, recall that the status of women relative to men is not higher in societies in which women contribute a lot to primary subsistence activities. Indeed, bride price is likely to occur in societies in which men make most of the decisions in the household,36 and decision making by men is one indicator of lower status for women.

In one Sudanese society the amount of bride price varies by height. A tall girl may bring 150 cows, a short girl just 30.

Bride Service

The next most common type of economic transaction at marriage— occurring in about 19 percent of the societies with economic transactions—requires the groom to provide bride service, or work for the bride’s family, sometimes before the marriage begins, sometimes after. Bride service varies in duration. In some societies, it lasts for only a few months; in others, as long as several years. Among the North Alaskan Eskimo, for example, the boy works for his in-laws after the marriage is arranged. To fulfill his obligation, he may simply catch a seal for them. The marriage may be consummated at any time while he is in service.37 In some societies, bride service sometimes substitutes for bride price. An individual might give bride service to reduce the amount of bride price required. Native North and South American societies were likely to practice bride service, particularly if they were egalitarian food collectors.38

Exchange of Females

Of the societies that have economic transactions at marriage, 6 percent have the custom whereby a sister or female relative of the groom is exchanged for the bride. Among the societies that practice exchange of females are the Tiv of West Africa and the Yanomamö of Venezuela and Brazil. These societies tend to be horticultural and egalitarian, and their women make a relatively high contribution to primary subsistence.39

Gift Exchange

The exchange of gifts of about equal value by the two kin groups about to be linked by marriage occurs somewhat more often (about 11 percent of those with economic transactions) than the exchange of females.40 Among the Andaman Islanders, for example, as soon as a boy and girl indicate their intention to marry, their respective sets of parents cease all communication and begin sending gifts of food and other objects to each other through a third party. The gift exchange continues until the marriage is completed and the two kin groups are united.41

Dowry

A substantial transfer of goods or money from the bride’s family to the bride, the groom, or the couple is known as a dowry.42 Unlike the types of transactions we have discussed so far, the dowry, which is given in about 8 percent of societies with economic transactions, is usually not a transaction between the kin of the bride and the kin of the groom. A family has to have wealth to give a dowry, but because the goods go to the new household, no wealth comes back to the family that gave the dowry. Payment of dowries was common in medieval and Renaissance Europe, where the size of the dowry often determined the desirability of the daughter. The custom is still practiced in parts of eastern Europe and in sections of southern Italy and France, where land is often the major item the bride’s family provides. Parts of India also practice the dowry.

In contrast to societies with bride price, societies with dowry tend to be those in which women contribute relatively little to primary subsistence activities, there is a high degree of social stratification, and a man is not allowed to be married to more than one woman simultaneously.43 Why does dowry tend to occur in these types of societies? One theory suggests that the dowry is intended to guarantee future support for a woman and her children, even though she will not do much primary subsistence work. Another theory is that the dowry is intended to attract the best bridegroom for a daughter in monogamous societies with a high degree of social inequality. The dowry strategy is presumed to increase the likelihood that the daughter and her children will do well reproductively. Both theories are supported by recent cross-cultural research, with the second predicting dowry better.44 But many stratified societies in which women and men have only one spouse at a time (including our own) do not practice dowry. Why this is so still needs to be explained.

Indirect Dowry

The dowry is provided by the bride’s family to the bride, the groom, or the couple. But sometimes the payments to the bride originate from the groom’s family. Because the goods are sometimes first given to the bride’s father, who passes most if not all of them to her, this kind of transaction is called indirect dowry.45 Indirect dowry occurs in about 12 percent of the societies in which marriage involves an economic transaction. For example, among the Basseri of southern Iran, the groom’s father assumes the expense of setting up the couple’s new household. He gives cash to the bride’s father, who uses at least some of the money to buy his daughter household utensils, blankets, and rugs.46