The Medicalization of Sex and Gender

9.1.4 Understand how the social response to intersex variations of anatomy reveal the social construction of sex and gender.

One major contribution of cross-cultural research has been to challenge the “natural” dichotomy of two biological sexes (male and female) and two gender identities (masculinity and femininity). Some biologists have pointed out that even the simple dichotomy of male and female sex fails to capture all the various possible experiences in between, as for example with people with intersex traits, whose genital anatomy is in between male and female types or whose genetics include a mixture of female XX chromosomes and male XY ones. There are a variety of intersex traits that situate some people as not easily categorized as either biologically male or female. In the United States, the division between biological male and biological female is sometimes blurry. A small percentage of people are born intersex—that is, their biological sex is ambiguous enough as to be impossible to categorize as either male or female. One in about 1,500 babies are born with something that qualifies as an intersex trait (Fausto-Sterling 2000). The vast majority of these births are ones involving genital ambiguity; it is far rarer for people to have a chromosomal type other than XX (female) or XY (male), although they do exist. This means that the odds that you know someone who might be classified as intersex to some degree are good. This also means, as with all forms of identity and inequality, that it is an issue that deserves our understanding and respect.

Different cultures have made sense of people that have intersex traits in different ways throughout time. Although acknowledged and revered in some societies throughout time, they have been concealed and medically “managed” in others. And even in societies in which intersex infants are medically managed, it is not always in precisely the same ways (Dreger 1998). For instance, while there are dozens of conditions that qualify bodies as “intersexed,” only a small minority of conditions that qualify as intersex require some type of surgical or medical intervention in early infancy or childhood. Yet, it has long been true that intersex infants have undergone surgeries dangerously early in the course of their lives in ways that help preserve the gender binary—that idea that there are two (and only two) types of people: men and women.

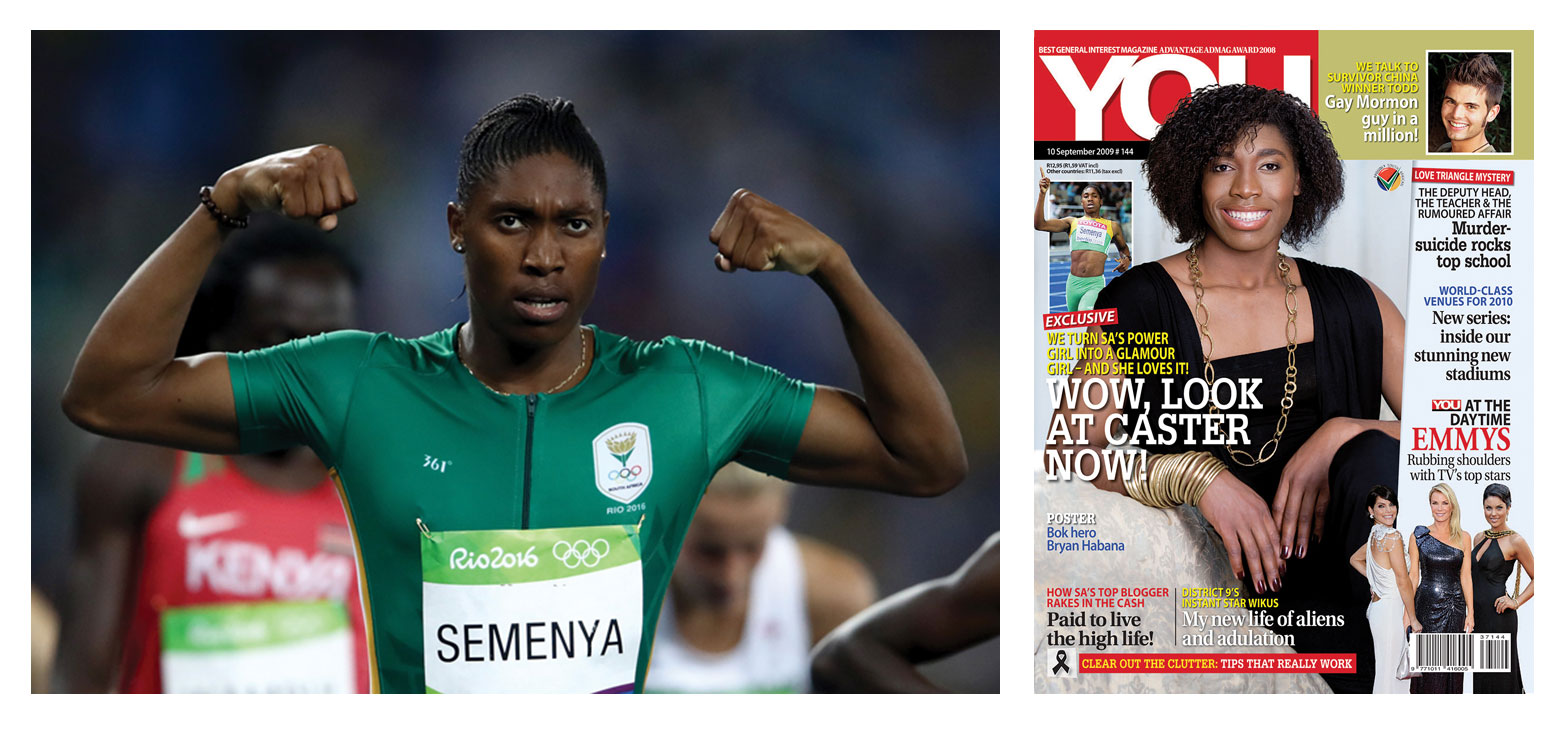

Semenya is here depicted racing and responding to the sex test she was forced to endure to continue competing alongside other women. What kinds of social pressures might have encouraged Semenya to align her presentation of self with “feminine” comportment and style following her highly publicized “sex verification test”?

Infants born with intersex traits is more common than you think. One way we often hear about it is when a professional athlete’s sex is called into question. The International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) and the International Olympic Committee (IOC) sometimes ask athletes to undergo “sex testing” to determine whether or not they ought to be allowed to compete. Take the case of 18-year-old Caster Semenya, a middle-distance runner from South Africa, who literally “ran away” with the world record in the 800-meter race at the 2009 World Championships in Track and Field. After the race, her biological sex was challenged by a defeated rival and the IAAF required Semenya to submit to a sex test. Semenya “passed” her sex test and continues to compete today. Indeed, Semenya ran away with the gold medal for the 800-meter race in the 2016 Olympics in Rio de Janeiro. Sex verification cases brought against athletes by the IAAF are exclusively brought against athletes competing as women. Charges are typically—though not always—brought when the athletes in question begin to break records. Consider the collection of beliefs about gender behind this pattern of sex testing athletes.

Sociologists of sex and gender are interested in studying how societies respond to diversity in sex development because it illustrates the social construction of both gender and sex. Like people whose racial and ethnic identities do not neatly map onto available categories mentioned in Chapter 8, people with intersex traits also offer us a powerful picture of how much work it takes to fit everyone into categories that do not actually encompass everyone. Some scholarship examines the ways that process of “medicalization” as it relates to sex and gender (Kessler 1998; Fausto-Sterling 2000). Medicalization refers to the process by which human conditions comes to be defined and treated as medical conditions such that they also become subject to medical study, diagnosis, and treatment. For a long time, it was not uncommon for medical professionals to surgically alter intersex bodies such that they conformed to the two-sex system—often without parents, and nearly always without the children themselves, completely understanding what is happening. When this happens, sex has become “medicalized.” Today, social activists fighting for the rights of people with intersex traits argue that surgical interventions are dangerous and unnecessary. And sociologists study the social movements and identity-based activism among people with intersex traits and their allies as well (Preves 2003; Davis 2015).

Some anthropologists discuss sex and gender in similar ways, suggesting that there may be far more sexes and genders out there than we acknowledge. Simply put, some cultures recognize more options than only two; other cultures recognize the possibility of being more than one (see MAP 9.1). Some societies do recognize more than two genders—sometimes three or four. The Navajo appear to have three genders—one for masculine men, one for feminine women, and one called nadle for those whose sex is ambiguous at birth. One can be born or choose to be nadle; they perform tasks for both women and men and dress in either men’s or women’s clothing according to the tasks they are performing. And they can marry either men or women. This illustrates that both sex and gender are best understood across a spectrum—rather than as discrete categories. Hijras in India occupy a similar space in Indian society, as a third gender category.

MAP 9.1 Mapping Gender-Diverse Cultures Around the World

Throughout recorded history, a diversity of cultures around the world have recognized more than two sexes or genders. Indeed, in many cultures, individuals occupying a category other than man or woman have been given high social status. In some, more than two genders are not only recognized, but are also fully integrated into the society. Globally, the variety of ways that different societies have recognized more than two genders is incredible. See this interactive map to learn more about gender variation around the world. NOTE: This is not an exhaustive list of gender diversity around the world or throughout time.

Source: Data from PBS, Independent Lens. “A Map of Gender-Diverse Cultures,” August 11, 2015. Available at http:/

Portrait of an Indian Hijra dressed up for a dancing performance.

Numerous cultures have a clearly defined gender role for what people who live outside the gender binary as contemporary U.S. society (along with many others) defines it. These are members of one biological sex who take the social role of the other sex, usually a biological male who dresses and acts as a woman. In most cases, they are not treated as freaks or deviants but are revered as special and enjoy high social and economic status; many even become shamans or religious figures (Williams 1986). People with intersex traits are a powerful example of the fact that not everyone fits into the gender binary, but also that our society is organized around a gender binary despite the fact that our bodies and biology sometimes resist the system of sex and gender classification in place.