2.3 Structure in the International System

-

Differentiate types of structure and describe how they help shape outcomes in the international system.

Structure is a set of overarching principles, rules, roles, and constraints that bind actors together into a larger system. It can organize or order actors into different relative positions of strength, wealth, influence, and status. It can help set the interests of actors and how they respond to each other in the system. Structural pressures can create unintended outcomes by imposing behavioral regularities and outcomes within the system. As we will see shortly, states that wish to cooperate with each other may fail to do so because of the political challenges created by structural properties of the international system, like anarchy. For all these reasons, the elements of structure exist independently of any one actor in a system.

This section provides multiple examples of international structure while identifying two attributes that help categorize different types of structure. The first highlights the relative importance of material or ideational components of international structure. A second differentiates structure according to whether it constrains the behavior of actors or constitutes some of the most prominent characteristics of actors, like their interests or their identity.

Some views hold that structure primarily consists of material factors. These are attributes associated with the physical world. They might include the distribution of military power, the distribution of wealth, or biological/genetic characteristics that motivate human action. Alternative conceptions of structure hold instead that the physical world only acquires meaning and the capacity to influence behavior through the ideas and understanding of humans. Accordingly, these collectively held ideas serve as knowledge that then creates the meaning and constraints the physical world imposes on human behavior.

You can begin to understand this distinction between material and ideational conceptions of structure through a thought exercise that imagines how the presence of a gun might structure the social interactions of a small group of people. A focus on a gun’s physical characteristics, namely its capacity to impose significant physical harm, suggests that it can be exploited to create a severe power imbalance within any group of people. Its possessor could use the gun to force others into fulfilling some set of demands by threatening death for noncompliance. In strictly material terms, a gun is likely to be viewed in threatening terms.

An alternative ideational conception suggests that the power of the gun created by its physical characteristics cannot be separated from the meaning or social context into which it is inserted. Consequently, the identity of the gun holder along with the social roles that he or she might possess instead sets the influence of the gun on any social interaction. For example, one person may simply be showing a gun to two close friends during a break at an evening dinner party. The gun here is not being exploited to make some set of coercive demands. Instead, it is a prop to relay a story about a prior hunting experience. A long history of friendship within the members of a group and a shared affinity for hunting eliminates any potential for the gun to possess some coercive capacity.

VIEW

When are Guns Threatening?

Compare these images of guns and think about how the level of threat associated with each of them might change depending on how participants and observers understand these settings.

We can see the relevance of this distinction between material and ideational conceptions of structure for international relations by replacing the gun with a nuclear weapon in the thought exercise. Some scholars argue that the possession of nuclear weapons is a powerful device to strengthen national security. It eliminates the capacity of all other states to achieve their political goals through a conventional military invasion.6 That invasion would simply prompt a nuclear retaliation that imposes unacceptable costs. Accordingly, the possession of nuclear weapons acts as a structural constraint on the behavior of all states in the international system. It shapes their political relations by altering their capacity to coerce others with military force. The political interests, identity, or regime type of the state possessing nuclear weapons is irrelevant. The absolute nature of the weapon’s physical destructiveness forces all states to treat those possessing nuclear weapons differently.

Alternatively, an ideational conceptualization of how nuclear weapons structure international politics might note how the United States treats an ally with nuclear weapons, such as the United Kingdom, differently from Iran. While Iran’s attempt to acquire nuclear weapons prompted the United States and Israel to consider a preventive military strike, the United States has long viewed British possession of nuclear weapons in more positive terms. These weapons could help an ally protect itself. Accordingly, different assessments of the national interests and identity of states—judgments that are rooted in ideational concepts like the presence or absence of shared social or cultural ties—might shape the political significance of nuclear weapons.

WHEN ARE NUCLEAR WEAPONS THREATENING? In November 2018, German Chancellor Angela Merkel and French President Emmanuel Macron commemorate the end of World War I and the long-term reconciliation between France and Germany after World War II. Even though France possesses nuclear weapons and these two countries have fought horrible wars against each other, Germany does not view France as a security threat.

AP Photo/Michel Euler

WATCH When Are Nuclear Weapons Threatening?

In his speech before the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) in March of 2015, the prime minister of Israel, Benjamin Netanyahu, sharply criticizes the pending Iran nuclear deal and describes the threat posed by Iran’s potential acquisition of nuclear weapons.

Getty Images

Second, attributes of international political structure can be differentiated according to the mechanisms by which they shape behavioral choices and outcomes in the international system. IR scholars generally focus on two primary mechanisms. In the first, the effects of structure are more direct. Structure either constrains or enables the behavior of individuals or governments. In this sense, the choices that people make depend on the penalties or rewards that structure imposes. In the negative form of this direct relationship, structure exists as some generalized threat or expectation that prohibited behavior will elicit retaliatory penalties.

The concentration of global economic wealth in one large state is an important component of international political structure.7 This hegemon can pressure other governments into reducing their tariff barriers to international trade by denying foreign exporters access to its domestic market. Accordingly, this concentration of economic power in the system can facilitate higher levels of international trade as the hegemon pressures other states to eliminate tariffs. Alternatively, the absence of a dominating state capable of pressuring other governments into cutting their tariffs can reduce global trade flows.

Similarly, there is a strong norm encouraging respect for territorial borders that discourages states from seizing the territory of other states.8 Iraq’s violation of this norm via its invasion of Kuwait in the summer of 1990 prompted a counterattack by the United States to restore Kuwaiti control over all its territory. The enforcement of this norm reaffirmed the costs of violating it and, potentially, helped deter similar attempts in the future.

Structure also influences behavior indirectly, by first helping to constitute the actors of a system and some of their fundamental properties. In a constitutive relationship, the actor and the structure are inseparable. The existence of an actor and its attributes, like its identity or interests, depends on and is enabled by the content of the larger structure. We can use the U.S. Constitution to illustrate a constitutive relationship. That document is a series of rules that structure political relationships within the United States. As a consequence, it defines the government of the United States and the important political actors within it, like the president, the House of Representatives, and the Senate. The removal of important components of the U.S. Constitution, like the first ten amendments known as the Bill of Rights, would make the United States a very different political organization. In this sense, the Constitution structures political relationships inside and outside the United States by constituting important political actors (literally making them possible), like the president and members of Congress.

THE U.S. CONSTITUTION By defining relationships among U.S. citizens and different branches of the federal government of the United States, the U.S. Constitution literally constitutes important international political actors—like the U.S. president—and their political interests, which might include reelection.

Pamela Au/Shutterstock

We can identify constitutive relationships created by structure with a simple question: Does some relationship with structure leave an actor unchanged? When structure constrains, an actor’s behavior is limited. However, its defining attributes, like its capabilities or interests, remain the same. When structure constitutes, these important attributes of the actor change.

A brief discussion of the European Union (E.U.) can illustrate some of these differences in the consequences of structure. It includes a common monetary system, organized around a common currency called the euro. Members of the European Union, like France and Germany, do not have their own currencies. Instead, they delegate responsibility for monetary policy to a European Central Bank. These monetary arrangements structure economic policymaking in Europe. Even though some governments might have an interest in tolerating higher levels of inflation to keep unemployment low, the rules associated with the European Monetary Union constrain them from doing so. The power to influence interest rates and inflation lies instead with the European Central Bank.

At the same time, a series of international organizations associated with the development of the European Union—like the European Coal and Steel Community, the European Parliament, and the European Court of Justice—have arguably helped to forge a common European identity held by elected politicians and citizens across Europe.9 The emergence of this collective European identity has transformed the national interests of individual states. In the midst of the recent euro financial crisis, German leaders supported a series of financial aid packages distributed to the Greek government to preserve its membership in the European Union and the broader political union itself. Thus, a wide-ranging political, economic, and social structure associated with the European Union has helped to create and sustain strong interests for important members like France and Germany in preserving the broader political community of Europe.

GREECE AND THE EURO CRISIS European leaders, including Angela Merkel (Germany), George Papandreou (Greece), and Nicolas Sarkozy (France) meet in Belgium in February 2010. They sought to construct an aid package that would keep Greece in the European Monetary Union, reduce the selling pressure on the euro, and curtail exploding budget deficits in Greece.

AP Photo/Virginia Mayo

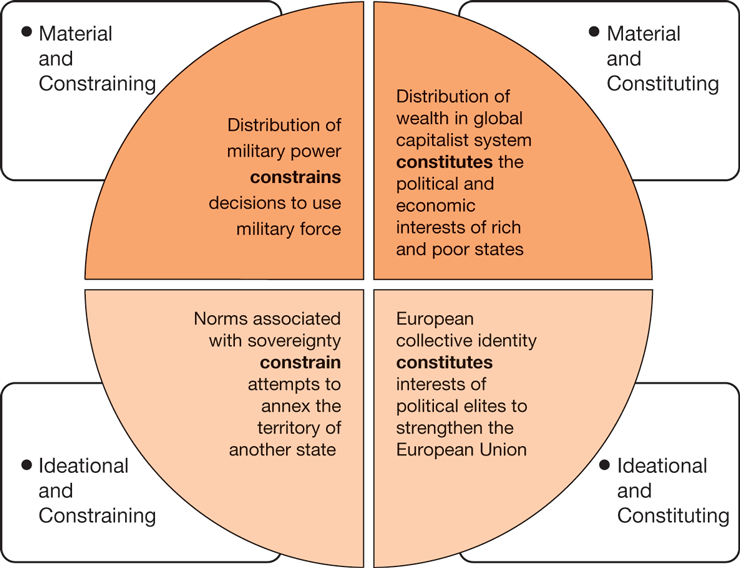

Based on this two-dimensional typology of structure, international political structure exists in at least four forms—material and constraining; ideational and constraining; material and constitutive; ideational and constitutive (see Figure 2.5). In Modules 4 through 6, we will see that these four conceptions help differentiate prominent theoretical traditions in the study of international relations.

Figure 2.5:

Four Types of International Structure

International structure is often distinguished by two characteristics—whether it is comprised by material or ideational factors; or whether it constrains or constitutes actors in the system.

Source: Pearson Education