Attention

LO 6.2 Define attention. Discuss Broadbent and Treisman’s theories of attention. Explain what is meant by the “cocktail-party phenomenon” and “inattentional blindness.”

Why does some information capture our attention, whereas other information goes unnoticed?

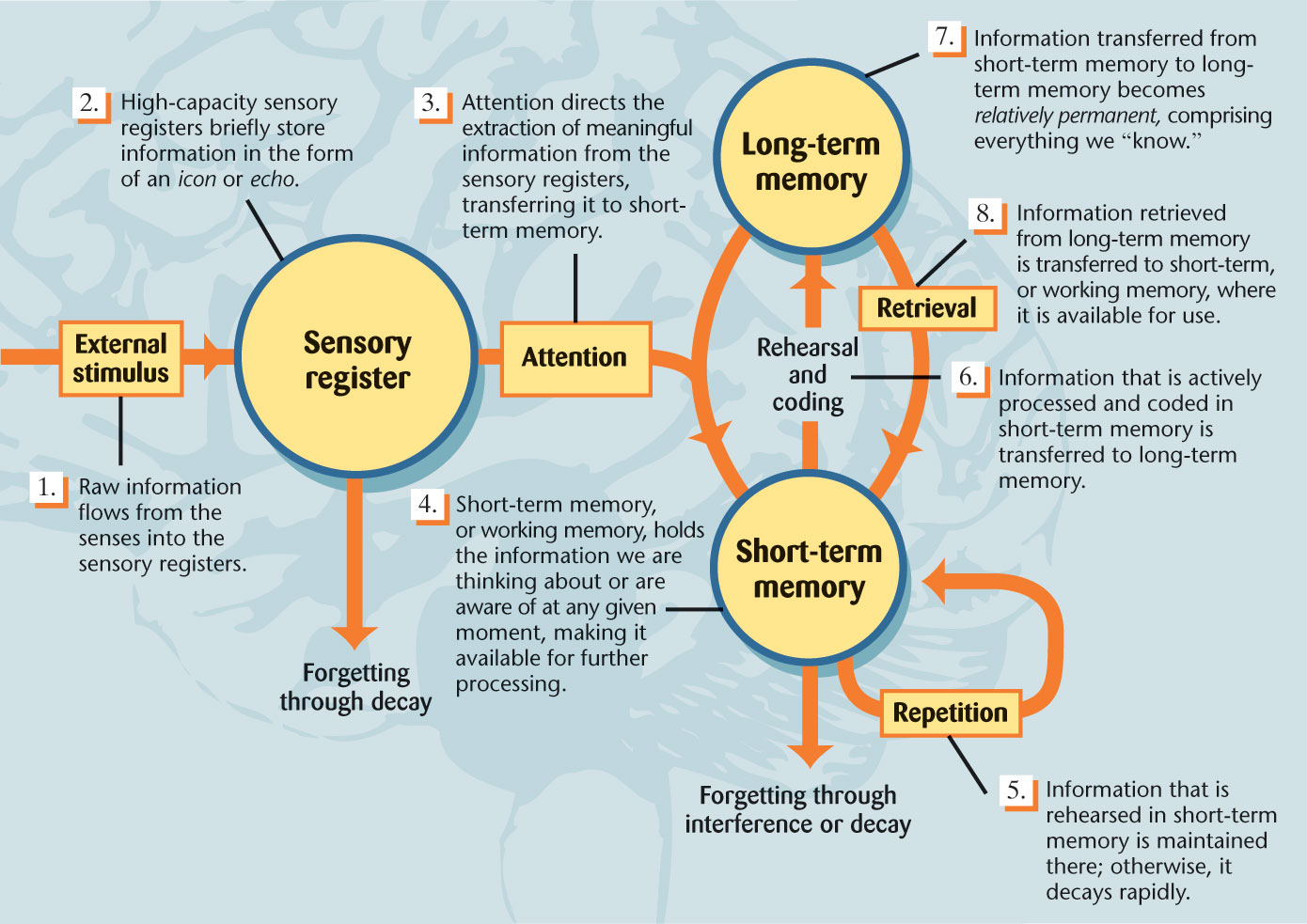

If information disappears from the sensory registers so rapidly, how do we remember anything for more than a second or two? One way is that we select some of the incoming information for further processing by means of attention (See Figure 6.1). Attention is the process of selectively looking, listening, smelling, tasting, and feeling. At the same time, we give meaning to the information that is coming in. Look at the page in front of you. You will see a series of black lines on a white page. For you to make sense of this jumble of data, you process the information in the sensory registers for meaning.

Figure 6.1

The Sequence of Information Processing

How do we select what we are going to pay attention to at any given moment, and how do we give that information meaning? Donald Broadbent (1958) suggested that a filtering process at the entrance to the nervous system allows only those stimuli that meet certain requirements to pass through. Those stimuli that do get through the filter are compared with what we already know, so that we can recognize them and figure out what they mean. If you and a friend are sitting in a restaurant talking, you filter out all other conversations taking place around you, a process known as the cocktail-party phenomenon (Cherry, 1966; Haykin & Chen, 2006). Although you later might be able to describe certain characteristics of those other conversations, such as whether the people speaking were men or women, according to Broadbent, you normally cannot recall what was being discussed, even at neighboring tables. Since you filtered out those other conversations, the processing of that information did not proceed far enough for you to understand what you heard.

Broadbent’s filtering theory helps explain some aspects of attention, but sometimes unattended stimuli do capture our attention. To return to the restaurant example, if someone nearby were to mention your name, your attention probably would shift to that conversation. Anne Treisman (1964, 2012) modified the filter theory to account for phenomena like this. She contended that the filter is not a simple on-and-off switch, but rather a variable control—like the volume control on a radio, which can “turn down” unwanted signals without rejecting them entirely. According to this view, although we may be paying attention to only some incoming information, we monitor the other signals at a low volume. Thus, we can shift our attention if we pick up something particularly meaningful. This automatic processing can work even when we are asleep: Parents often wake up immediately when they hear their baby crying, but sleep through other, louder noises.

At times, however, our automatic processing monitor fails, and we can overlook even meaningful information. In research studies, for example, some people watching a video of a ball-passing game failed to notice a person dressed as a gorilla who was plainly visible for nearly 10 seconds (Drew, Võ, & Wolfe, 2013; Mack, 2003). In other words, just because we are looking or listening to something, doesn’t mean we are attending to it. Psychologists refer to our failure to attend to something we are looking at as inattentional blindness. Research has shown, for example, that attending to auditory information can reduce one’s ability to accurately process visual information, which makes driving while talking on a cell phone a distinctly bad idea (Pizzighello & Bressan, 2008)!