Experience and Forgetting

LO 6.10Describe non-biological factors that can contribute to forgetting. Differentiate between retroactive and proactive interference.

What environmental factors contribute to our inability to remember?

Although sometimes caused by biological factors, forgetting can also result from inadequate learning. A lack of attention to critical cues, for example, is a cause of the forgetting commonly referred to as absentmindedness. For example, if you can’t remember where you parked your car, most likely you can’t remember because you didn’t pay attention to where you parked it.

Forgetting also occurs because, although we attended to the matter to be recalled, we did not rehearse the material enough. Merely “going through the motions” of rehearsal does little good. Prolonged, intense practice results in less forgetting than a few, halfhearted repetitions. Elaborative rehearsal can also help make new memories more durable. When you park your car in space G-47, you will be more likely to remember its location if you think, “G-47. My uncle George is about 47 years old.” In short, we cannot expect to remember information for long if we have not learned it well in the first place.

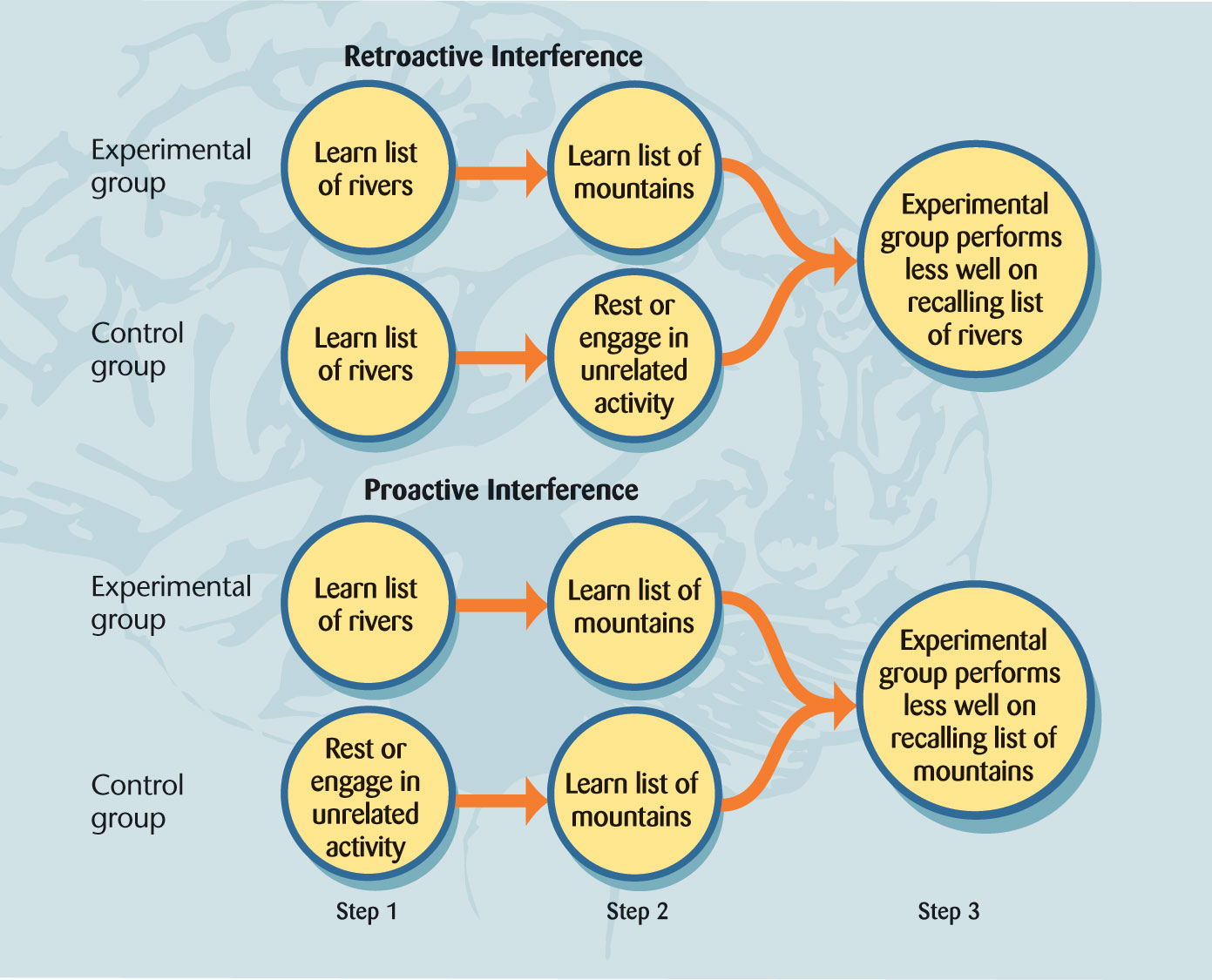

Interference Inadequate learning accounts for many memory failures, but learning itself can cause forgetting. This is the case because learning one thing can interfere with learning another. Information gets mixed up with, or pushed aside by, other information and thus becomes harder to remember. Such forgetting is said to be due to interference. As portrayed in Figure 6.7, there are two kinds of interference. In retroactive interference, new material interferes with information already in long-term memory. Retroactive interference occurs every day. For example, once you learn a new telephone number, you may find it difficult to recall your old number, even though you used that old number for years.

In the second kind of interference, proactive interference, old material interferes with new material being learned. Like retroactive interference, proactive interference is an everyday phenomenon. Suppose you always park your car in the lot behind the building where you work, but one day all those spaces are full, so you have to park across the street. When you leave for the day, you are likely to head for the lot behind the building—and may even be surprised at first that your car is not there. Learning to look for your car behind the building has interfered with your memory that today you parked the car across the street.

The most important factor in determining the degree of interference is the similarity of the competing items. Learning to swing a golf club may interfere with your ability to hit a baseball, but probably won’t affect your ability to make a free throw on the basketball courts. The more dissimilar something is from other things that you have already learned, the less likely it will be to mingle and interfere with other material in memory (G. H. Bower & Mann, 1992).

Figure 6.7

Diagram of Experiments Measuring Retroactive and Proactive Interference.

In retroactive interference, the experimental group usually does not perform as well on tests of recall as those in the control group, who experience no retroactive interference from a list of words in Step 2. In proactive interference, people in the experimental group suffer the effects of proactive interference from the list in Step 1. When asked to recall the list from Step 2, they perform less well than those in the control group.