The Earliest Public Opinion Research

The Earliest Public Opinion Research10.1 Trace the development of modern public opinion research.

At first glance, public opinion seems to be a straightforward concept: it is what the public thinks about a particular issue or set of issues at any point in time. In government and politics, for example, researchers measure citizens’ views on candidates, political institutions, and policy proposals. Since the 1930s, governmental decision makers have relied heavily on public opinion polls—interviews with samples of citizens that estimate the feelings and beliefs of larger populations, such as all Americans or all women. According to George Gallup (1901–1983), an Iowan who is considered the founder of modern-day polling, polls have played a key role in defining issues of concern to the public, shaping administrative decisions, and helping “speed up the process of democracy” in the United States.1

Gallup further contended that leaders must constantly take public opinion—no matter how short-lived—into account. This practice does not mean that leaders must follow the public’s view slavishly; it does mean, however, that they should have an available appraisal of public opinion and consider it in reaching their decisions. Politicians may find this process challenging when public opinion appears split on an issue or is in opposition to their views.

Even though Gallup, as a pollster, undoubtedly had a vested interest in fostering reliance on public opinion polls, his sentiments accurately reflect the views of many political thinkers concerning the role of public opinion in governance. Some commentators argue that the government should do what a majority of the public wants done. Others argue that the public as a whole doesn’t have consistent day-to-day opinions on issues but that subgroups within the public often hold strong views on some issues. These pluralists believe that the government must allow for the expression of minority opinions and that democracy works best when different voices are allowed to fight it out in the public arena, echoing James Madison in Federalist No. 10.

The Earliest Public Opinion Research

The Earliest Public Opinion ResearchAs early as 1824, one Pennsylvania newspaper tried to predict the winner of that year’s presidential contest, showing Andrew Jackson leading over John Quincy Adams. In 1883, the Boston Globe sent reporters to selected election precincts to poll voters as they exited voting booths, in an effort to predict the results of key contests. Public opinion polling as we know it today really began to develop in the 1930s. Walter Lippmann’s seminal work, Public Opinion (1922), prompted much of this growth. Lippmann observed that research on public opinion was far too limited, especially in light of its importance. Researchers in a variety of disciplines, including political science, heeded Lippmann’s call to learn more about public opinion. Some tried to use scientific methods to measure political thought through the use of surveys or polls. As methods for gathering and interpreting data improved, survey data began to play an increasingly significant role in all walks of life, from politics to retailing.

Literary Digest, a popular magazine that first began national presidential polling in 1916, was a pioneer in the use of the straw poll, an unscientific survey used to gauge public opinion, to predict the popular vote, which it did, for Woodrow Wilson. Its polling methods were hailed widely as “amazingly right” and “uncannily accurate.”2 In 1936, however, its luck ran out. Literary Digest predicted that Republican Alfred M. Landon would beat incumbent President Franklin D. Roosevelt by a margin of 57 percent to 43 percent of the popular vote. Roosevelt, however, won in a landslide election, receiving 62.5 percent of the popular vote and carrying all but two states.

Literary Digest’s 1936 straw poll had three fatal errors. First, it drew its sample, a subset of the whole population selected to be questioned for the purposes of prediction or gauging opinion, from telephone directories and lists of automobile owners. This technique oversampled the upper middle class and the wealthy, groups heavily Republican in political orientation. Moreover, in 1936, voting polarized along class lines. Thus, the oversampling of wealthy Republicans was particularly problematic because it severely underestimated working class Democratic voters, who had neither cars nor telephones.

Literary Digest’s second problem was timing. The magazine mailed its questionnaires in early September. This did not allow the Digest to measure the changes in public sentiment that occurred as the election drew closer.

Its third error occurred because of a problem we now call self-selection. Only highly motivated individuals sent back the cards—a mere 22 percent of those surveyed responded. Those who answer mail surveys (or today, online surveys) are quite different from the general electorate; they often are wealthier and better educated and care more fervently about issues. Literary Digest, then, failed to observe one of the now well-known cardinal rules of survey sampling: “One cannot allow the respondents to select themselves into the sample.”3

The Gallup Organization

The Gallup OrganizationAt least one pollster, however, correctly predicted the results of the 1936 election: George Gallup. Gallup had written his dissertation in psychology at the University of Iowa on how to measure the readership of newspapers. He then expanded his research to study public opinion about politics. He was so confident about his methods that he gave all of his newspaper clients a money-back guarantee: if his poll predictions weren’t closer to the actual election outcome than those of the highly acclaimed Literary Digest, he would refund their money. Although Gallup under-predicted Roosevelt’s victory by nearly 7 percent, the fact that he got the winner right was what everyone remembered, especially given Literary Digest’s dramatic miscalculation.

Through the late 1940s, polling techniques increased in sophistication. The number of polling firms also dramatically rose, as businesses and politicians began to rely on polling information to market products and candidates. But, in 1948, the polling industry suffered a severe, although fleeting, setback when Gallup and many other pollsters incorrectly predicted that Thomas E. Dewey would defeat President Harry S Truman.

Not only did advance polls in 1948 predict that Republican nominee Thomas E. Dewey would defeat Democratic incumbent President Harry S Truman, but on the basis of early and incomplete vote tallies, some newspapers’ early editions published the day after the election declared Dewey the winner. Here a triumphant Truman holds aloft the Chicago Daily Tribune.

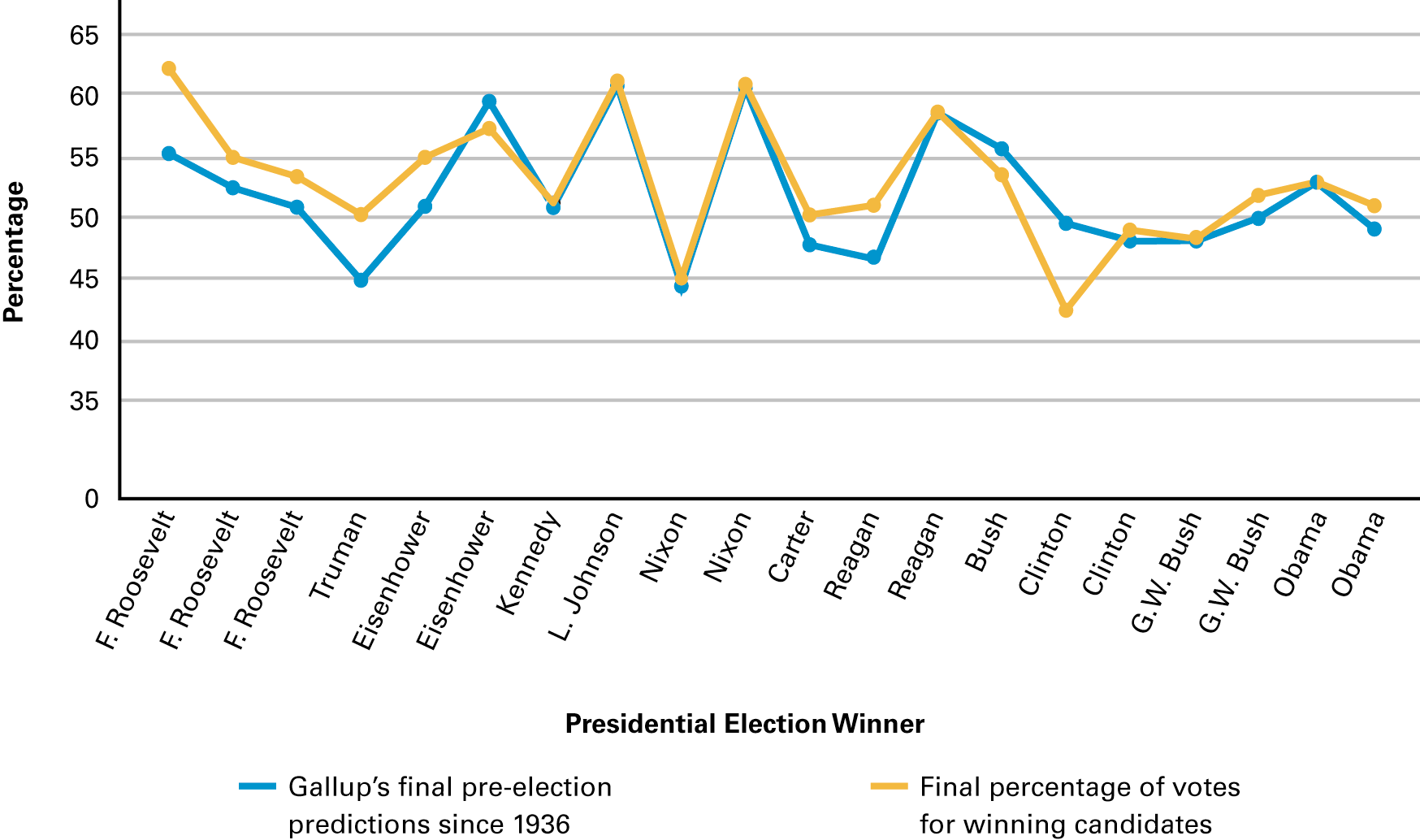

Nevertheless, as revealed in Figure 10.1, the Gallup Organization continues to make remarkably accurate predictions about the outcome of presidential elections. In 2012, the Gallup Poll predicted a virtual dead heat between Mitt Romney and Barack Obama; President Obama won 51 percent of the popular vote.

As seen here, Gallup’s final predictions have been remarkably accurate. Furthermore, in each of the years in which a significant discrepancy exists between Gallup’s prediction and the election’s outcome, a prominent third candidate factored in. In 1948, Strom Thurmond ran on the Dixiecrat ticket; in 1980, John Anderson ran as the American Independent Party candidate; in 1992, Ross Perot ran as an independent.

Sources: Marty Baumann, “How One Polling Firm Stacks Up,” USA Today (October 27, 1992): 13A; 1996 data from Mike Mokrzycki, “Pre-election Polls’ Accuracy Varied,” Atlanta Journal and Constitution (November 8, 1996): A12; 2000 data from Gallup Organization, “Poll Releases,” November 7, 2000; 2004, 2008, and 2012 data from USA Today and CNN/Gallup Tracking Poll, www.usatoday.com.

The American National Election Studies

The American National Election StudiesRecent efforts to measure public opinion also have benefited from social science surveys such as the American National Election Studies (ANES). The ANES have been conducted by researchers at the University of Michigan and Stanford University since 1952. Since 1977, they have been funded largely by the national government through the National Science Foundation. Focusing on the political attitudes and behavior of the electorate, ANES surveys include questions about how respondents voted, their party affiliation, and their opinions of major political parties and candidates. In addition, ANES surveys contain questions about interest in politics and political participation.

Researchers conduct ANES surveys before and after mid-term and presidential elections, often including many of the same questions. This format enables researchers to compile long-term studies of the electorate and facilitates political scientists’ understanding of how and why people vote and participate in politics.