5.1 Freedom or Empire?

-

By what means did the British government attempt to balance the imperial budget, and what was the American reaction?

Different Reactions to 1763

The victory of the British side in the French and Indian War—or Seven Years’ War—should have been a time for rejoicing in America and Britain alike. And it was, briefly. But the very fact that the war had different names in America and Europe hinted that the victory might have different meanings on the opposite sides of the Atlantic.

For the Americans, the victory signaled freedom from the threat that had hung over the frontier for a century: the threat of attack from Indians supported by France. With France evacuating Canada, the Indians would have little alternative to accepting the dominance of the American colonists. Life for the colonists would become more secure; new lands in the Ohio Valley would be opened to settlement. The American freedom won in the war would certainly expand in the decades ahead.

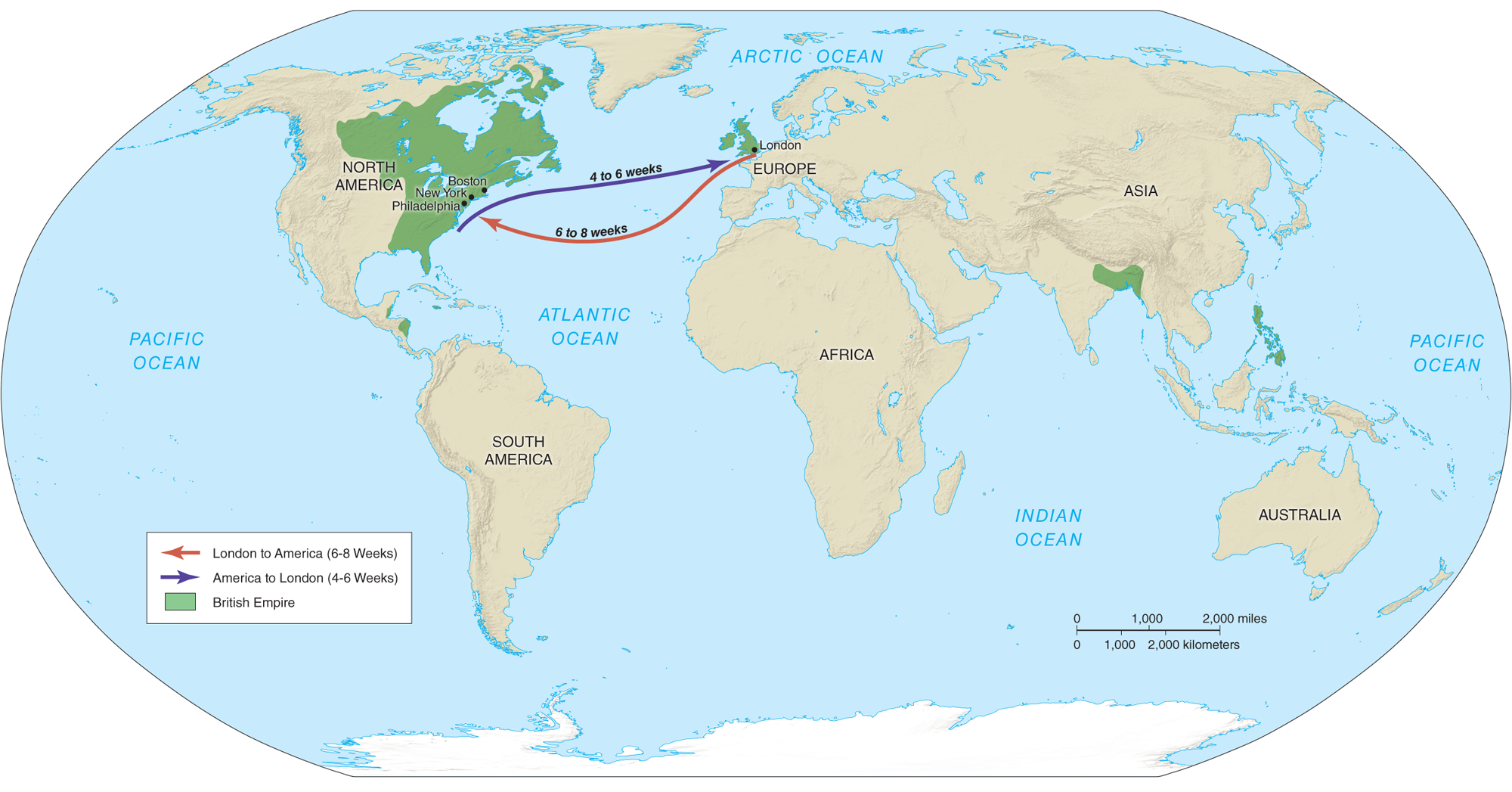

Map 5.1

The British Empire in 1763

Britain's far-flung colonies gave Britain great power, but the distances involved made communications slow and governance unwieldy.

The British saw things differently. North America was merely one part of Britain’s empire, and by no means the most important. India was the bigger prize. And there were considerations of politics in Europe, where the French were hardly at an end of their influence. Finance was no small matter, either. In the wake of the war, finance figured centrally in British thinking. The war had been extraordinarily expensive; the British government had taken on great debt to fund it. In the aftermath of the conflict, the first order of business for the British government was paying down the debt to secure the future of the empire.

THE GREAT FINANCIER (The illustration caption reads “The Great Financier, or British Economy for the Years 1763, 1764, 1765.”) After achieving victory, England had to increase its revenue to pay off the expenses incurred during the Seven Years’ War.

Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division [LC-USZ62-4539]

To reduce the imperial debt, the British began to do two things: cut spending and increase revenues. A major expense had long been the stationing of British army troops near the American frontier, and so the government ordered the closing of western forts and the withdrawal of the troops that had manned them. Some of the troops would remain in America, in coastal cities where they were less expensively supplied; others would be withdrawn from America entirely.

But the withdrawal posed a potential problem. If clashes arose between the American colonists and the Indians, there would be no troops to defend the colonists. And so the government took another step. It issued the Proclamation of 1763, which forbade the Americans from settling west of the Appalachian Mountains—that is, in the Ohio Valley. By keeping the Americans out, the British government reasoned, it would prevent new outbreaks of violence. This would be good for the Indians, good for the Americans, and good for the British budget.

Map 5.2

Proclamation Line of 1763

The Americans didn’t see things that way. What was the point, the Americans asked themselves, of their efforts in the recent war if they couldn’t enjoy the fruits of victory? Those who remembered how the British government had given back Louisbourg fifteen years earlier felt double-crossed again. Americans inclined to think the worst of London detected a deliberate attempt to hem them in along the coast, lest the American colonies become too powerful within the empire. Even Americans more charitably disposed toward the British government recognized that American interests were being sacrificed to larger imperial interests. For neither group did the proclamation sit well.

The Americans were still grumbling when they found more to grouse about. In 1764, Parliament passed the Sugar Act, which laid import duties on molasses. The colonists had a sweet tooth, but they also had a thirst—for the rum into which the molasses was fermented and distilled. The curious thing about the Sugar Act was that it lowered the rate of import tax the Americans would have to pay, and yet it provoked an uproar among those same Americans. The uproar resulted from the fact that the Americans had grown used to not paying any import tax at all. The previous rate had been so high that a large black market in smuggled molasses had developed, and most Americans got their molasses by this route.

The new Sugar Act lowered the rate to the point where smuggling, with its own costs and hazards, became uneconomical. The new act also included provisions for stiffer enforcement of the laws against smuggling. The result was that the smugglers were likely to be forced out of business, and molasses buyers would have to pay more for their molasses, which would translate into rum drinkers having to pay more for their rum. The smugglers couldn’t well complain without admitting that they were smugglers, nor those who benefited from the smuggling without admitting their complicity.

TARRING AND FEATHERING This political cartoon, showing the “exciseman” being tarred and feathered, depicts the outrage that many Americans felt about being subjected to taxation without representation.

Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division [LC-USZ62-33262]

But the Americans complained all the same. They bemoaned the insensitivity of Parliament to American practices; a few tossed about the term “tyranny.” Remarking on the traditionally loose rein London had allowed the colonies, they insisted that the reins remain loose. Some who had followed the debates in Parliament on the Sugar Act, including Benjamin Franklin, noted that the justification for the Sugar Act included the government’s need to raise revenue. Previous trade measures—or Navigation Acts, as they were called—had generally confined themselves to regulating commerce rather than raising revenue.

Taxes—that is, revenue—had been a sensitive point in English politics for centuries. Since the days of the Magna Carta, the 1215 charter that became the basis for parliamentary government, the principle had developed that the people could not be taxed without their consent—or, in practice, the consent of their representatives in Parliament. Americans observed that they had no representatives in Parliament, and some began saying that without representation there could be no taxation like that which the Sugar Act imposed.